Puerto Rico was one of the epicenters of the Classic Tainos civilization, along with surrounding Puerto Rican islands (Vieques, Culebra), Hispaniola (modern day Dominican Republic/Haiti), and parts of the Virgin Islands (St. Croix, St. John, St. Thomas, Tortola, etc.). The Tainos were an Arawakan people who had descended from peoples who migrated from South America throughout the years. There were variants of the Taino, Eastern Tainos (from the Virgin Islands southward), Classic Tainos (Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola), and Western Tainos (Jamaica, Cuba); however, the Classic Tainos were the most unfiltered and uninfluenced by surrounding tribes like the Eastern Tainos with the Caribs of the Lesser Antilles or the Western Tainos with the Guanahatabey of Cuba. The Classic Tainos were more developed culturally and linguistically and were “identified with the most complex and intensive traditions, and are represented archaeologically by “Chican-Ostionoid” material culture.” [1] The Chican era was a late part of the Ostioniod period which ran approximately from A.D. 600 to 1200.

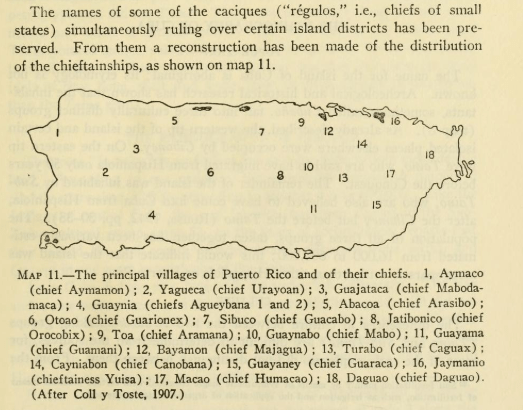

Remnants have been uncovered across the Caribbean and still continue to be discovered from these indigenous people. In the Greater Antilles where the Classic Tainos thrived, archaeological sites, petroglyphs, pottery fragments, and tools continue to be found. As well, much of the lexicon of today includes many integrated Taino words — Borikén (“the great land of the valiant and noble Lord”, Boriquen, Puerto Rico), canoa (canoe), Hurakán (hurricane and “god of the storm”), tuna (prickly pear), colibri (hummingbird), tabako (tobacco), wanaban (guanabana or soursop), papaya, yuca (cassava root), mamey, barbacoa (barbecue), cokí (coqui or small tree frog), iguana, hamaca (hammock), … In Puerto Rico the largest remnants have been uncovered as it was a central island for the Tainos, hosting about 18 caciques (chiefs) and their respective villages across the island. One such place was Otoao, modern day Utuado, located in the Cordillera Central (Puerto Rico’s centralized mountainous area), where the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park is located.

Caguana is one the largest and most complex indigenous ceremonial sites in the whole of the Caribbean. It is situated in the Tanama River Valley consists of a couple large plazas, 10 stone-lined ball courts (called bateys, named after the balls (batey) where a type of hand ball game was played), a ceremonial dancing court (called areyto, where song, dance and story came together for ceremonies), a religious mound, and many stone carved petroglyphs. From the archaeological work carried out in this site, it was concluded that this site had both pre-Taino and Taino remnants. In the Taino time, it was not a regular yucayeque (village) as it had been in the pre-Taino time, but more of a ceremonial site that was used for special occasions (and obviously batey games) by several surrounding villages and not a continuously occupied area. Some do speculate if the batey games were more of a way of settling disagreements, ownership issues, aliiances, etc., either way it was very central to their way of doing things and very much a ceremonial act.

Indigenous sites like this at Caguana provide great insight into the Tainos, which is one of the Caribbean’s closest and most influential ancestors to this day. It is interesting that most of their ancestors, both those coming from South America and Central America, have many similarities such as the plazas and ball courts. There is controversy regarding the “true” descendant lines of the Tainos, as Colombus was said to have eradicated them, however, many Puerto Ricans, along with others in the Classic Taino Greater Antilles area, have been found to have DNA linking them to the Tainos, South American and Central American indigenous ancestry.

Even though this site has been a National Register site since 1993, it is still not fully protected and free from threat, there is still harm from natural disasters like hurricanes which further degrade the site and stones, and also from the local government, who in early 2022 tried to transfer the ownership of the site from the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture to the City of Utuado, and as it was rumored, to make way for further development through privatization. This was met with a great fight of pro-Taino and Taino descendants who used the argument that an indigenous sacred site could never be private, and it seems to have been approved for the time being as of late 2022.

More needs to be done to maintain the preservation, safety, and well-being of these indigenous sites across the Caribbean, be it further education, advocacy, and potential grant funding. The more knowledge Caribbean people have of their ancestry and heritage, the more ownership, pride and stewardship comes into play. Speaking for myself, who has Taino and indigenous heritage in my ancestral lines via Puerto Rico, I look to these places as irreplaceable gifts to envision a part of what makes me. Not many have that. We owe it to future generations to do better and be better. We are not landowners, but caretakers.

[1] “Taíno Culture History.” Florida Museum, 7 Dec. 2018, https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/histarch/research/haiti/en-bas-saline/taino-culture/.

Discover more from Heritage Matters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.