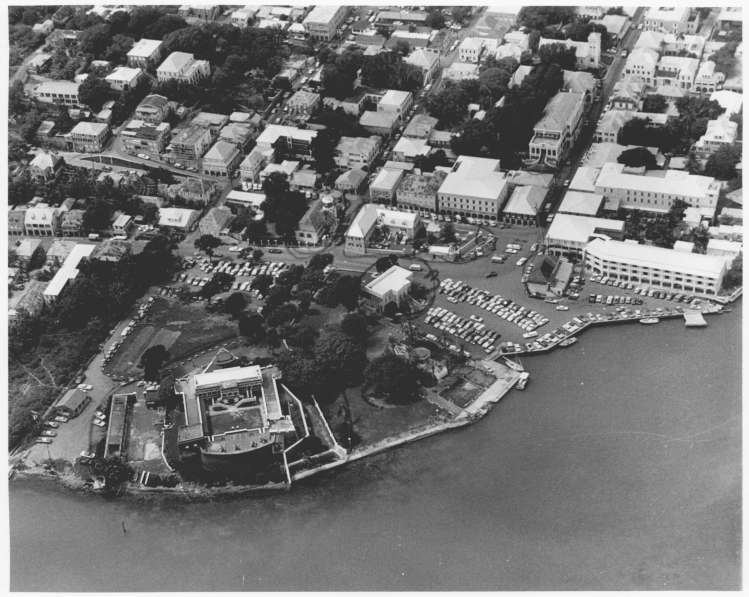

One of the earliest recorded National Register of Historic Places sites in the US Virgin Islands is that of Christiansted National Historic Site, located in none other than Christiansted, St. Croix. The site encompasses 6 historic structures on 7 acres along the waterfront. These structures being Fort Christiansvaern (b. 1738), Danish West India and Guinea Company Warehouse (b. 1750), the Steeple Building (b. 1753), Danish Customs House (b. 1734), the Scale House (b. 1856), and the Government House (1747). The buildings, together with the site, are an ever-present storyteller of the past transcending through time.

Christiansted National Historic Site Aerial View, 1976. (Photo credit: National Park Service)

St. Croix, more so than the other islands, was ruled by many nations and a total of 7 flags have flown over the island. St. Croix, originally inhabited by Arawak, Taino and Carib tribes before Columbus showed up in 1493, flew under Dutch, English, Spanish, French, Knights of Malta, Danish, and eventually US flags. St. Croix was uninhabited for quite a while after the small French colony that had settled on-island, evacuated to Hispaniola in the late 1600s amidst war between the English, Dutch and French. However, it would be the Danes who would leave their permanent mark on all the islands.

The waterfront wharf of Christiansted, 1800s. (Photo credit: Danish Maritime Museum)

The island was purchased by the Danish West India and Guinea Company* in 1733 and Christiansted would be founded by Lieutenant General Frederick von Moth, after being appointed governor shortly after. The Danish West India and Guinea Company seized on the untapped agricultural potential of St. Croix. Immediately the island was allocated a set number of both sugar and cotton plantations. According to the 1742 census, there were 120 sugar plantations, 122 cotton plantations, 1,906 slaves, 300 English, and 60 Danes. The following year St. Croix would get a hospital.[1]

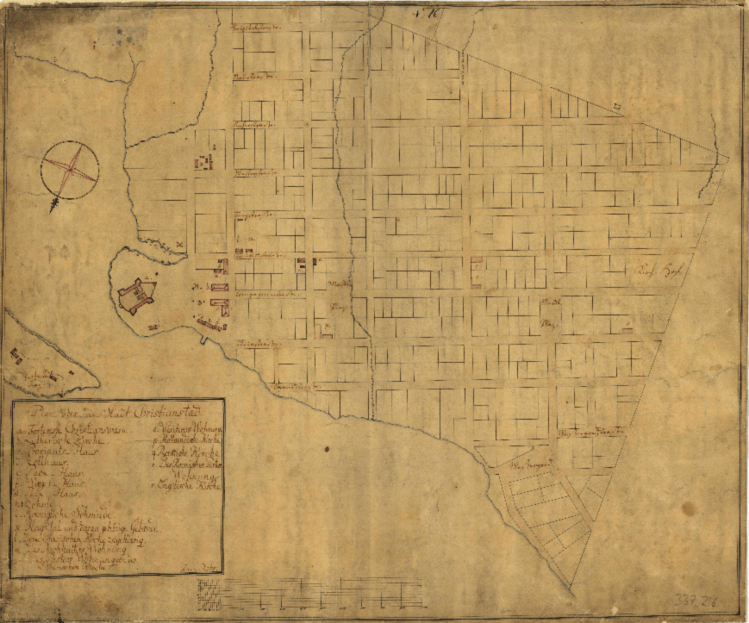

The city of Christiansted, which remains the largest city on St. Croix, was originally founded on a grid system on the remnants of what was previously the French colony called Bassin. Believe it or not, there was a building code and it dictated the specifications for construction and infrastructure down to the detail. Large bricks were brought over as ship’s ballast from Denmark while locally sourced rubble and coral from the harbor reefs were used as supplementary building materials. The architecture of the Danish West Indies was distinctively Danish colonial, as the local resources and local builders heavily impacted the fabric and final design of the buildings. In Christiansted this was more apparent as the town had a major African influence on the Danish colonial infrastructure and buildings due to the highly skilled African slave labor.

Danish map of Christiansted with the ‘Christiansted National Historic Site’ complex to the middle left of the map, 1750s. (Photo credit: The Danish Archives)

Fort Christiansvaern commenced construction in 1738 upon the remnants of a former French fortification, which had been destroyed by a hurricane. It would not be until 1749 that construction of the larger, yellow masonry fort would be complete. Its strategic location aided in shielding the city from hurricanes, pirates and possible slave revolts. It is built in a star-shape around an interior courtyard with enormous exterior, masonry walls. The fort would serve varied use throughout the years; however, initially it would be the holding station for all African slaves who were brought in on the slave ships. The holding station would later be removed from the fort and it would become home to the early governors, then the headquarters for the police, a jailhouse, a courthouse, court offices and the archives. It remains a wonderful example of Danish colonial military architecture and though federally owned, is under the management of the National Park Service and open to visitors.

Fort Christiansvaern (Photo credit: National Park Service)

Interior courtyard of Fort Christiansvaern. (Photo credit: National Park Service)

The Danish West India and Guinea Company Warehouse was built around 1750 and was the epicenter of all Danish trade and commerce throughout the 18th century. At this time in Danish West Indies’ history, St. Croix was the most successful of the three islands, and Christiansted was its capital. The warehouse itself is a complex consisting of 3 stuccoed, masonry buildings in Danish colonial architecture, with one being single level and the other two being two stories. The style is a bit unique as it incorporates 18th and 19th century architectural details. The main structure was the offices and base for the company. After the 1830s it became a depot for the Danish military, then a telegraph office, and it would later become the Post Office and Customs House after the US purchase.

Danish West India and Guinea Company Warehouse after it was transformed into the Post Office, 1974. (Photo credit: National Park Service)

The Steeple Building as it is now called, though previously identified as ‘The Church of Our Lord of Sabaoth’, finished construction in 1753. It was the religious heart of Christiansted as it was the official and only Danish Lutheran church on St. Croix. It was built as a one-story brick and rubble masonry building, with the tower as a later addition. It has very subtle baroque details, but for the most part remains quite simple in its architectural style and form. By the 1830s the church was sold to the government as growing congregation size forced them to relocate. The church was then turned into a military bakery with warehouse space. It would later function as a community center, a hospital and an elementary school. It was restored in the 1960s by the National Park Service and became a museum. The original furnishings were preserved by the Lutheran church congregation who moved it in its entirely to the new church.

The Steeple Building, formerly the Lutheran church ‘The Church of Our Lord of Sabaoth’. (Photo Credit: Lunn & Co, The West Indian Project)

The Customs House was where taxes were collected. It is situated between the Scale House and Fort Christiansvaern. The Customs House dates back to 1734, as it was originally a one-story residence for the Danish West India and Guinea Company’s bookkeeper. There were later additions in the 1840s, including the second story, when it became the Customs House. The building is made from stuccoed limestone and brick masonry. The building is uniquely both European and West Indian with its vernacular style and grand entrance facing the Christiansted waterfront. The Customs House would later become a Post Office before transitioning into a library. Now it remains closed to the public.

The Customs Building.

The Scale House was another major point of Danish commerce in the city; it was where imported goods were inspected and exported goods like sugar were weighed and taxed before passing through to Denmark, America and other European destinations. Construction was finished in 1956 and it was situated right on the waterfront amidst the bustling scene of trade. The ground floor is fabricated of brick masonry, while the second floor is wood construction. It is a straightforward functioning building devoid of style, unlike the other major commercial buildings on the wharf, but it played a very important role for daily life in Christiansted.

The rear of the Scale House.

Lastly but in no way the least, the Government House of Christiansted, which remains one of the largest governor’s residences throughout the Lesser Antilles. Originally the Schopen House, a Danish merchant’s home built in 1747, it was purchased by the Danish government in the 1770s and transitioned, with later additions, into a residence for the governor. Another adjacent house, the Søbøtkergaard House, which was built in the late 1790s, would be purchased by the government in the 1830s to add to the Government House for offices. The residence is u-shape in plan situated around a central courtyard. Due to the two different structures being constructed in different periods, the architectural styles vary between vernacular, baroque, and even Nordic influences.

Government House (Photo credit: Lunn & Co, The West Indian Project)

In 1871 the seat of power shifted from Christiansted to Charlotte Amalie, in St. Thomas. The Government House no longer ruled the islands; however, the residence retained its function as a government building and continues to host various social and cultural events. The original interior furnishings for the Governor’s House had been gifted from the Danish government, but when the Danish West Indies was transferred to a US territory in 1917, the Danes took the furnishings with them. Today there remain reproductions of the original Danish furnishings.

Interior courtyard of the Government House. (Photo credit: Lunn & Co, The West Indian Project)

Although centuries have passed, the Christiansted National Historic Site retains an impression of the former Danish stronghold. It was through the collective effort and concern of local citizens in 1952 that this 7-acre site could be preserved for future generations to witness a glimpse into history. Lest we forget that it was all made possible by the manpower of the highly skilled, enslaved Africans who put their literal blood, sweat and tears into their work as tradesman first and foremost. We owe it to them and to future generations to preserve that legacy, be it dark, be it heavy, history cannot be re-written and we must learn fully from the past to move forward. The site was later listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

*The Danish West India and Guinea Company was basically a royal Danish charter, which allowed them a complete national monopoly on trade and shipping, as long as they obliged to the King of Denmark’s requests. Their main objective was trading, colonization, and they played the role of slave trader, trading goods in return for slaves from Africa’s Gold Coast and bringing them to the new Danish colonies.

[1] Westergaard, Waldemar (1917). The Danish West Indies Under Company Rule (1671-1754). New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 209–217, 222–225, 235.

Discover more from Heritage Matters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.